VISIONS, FIRE, AND THE RESPONSIBITILY OF HAITIAN ART

by Gianick Barro

Watson Mere

Born in Belle Glade, Florida, to Haitian immigrants who worked the surrounding sugarcane fields, Watson Mere (b. 1987) absorbed a dual world of contrasts, an American life outside closed doors compared to a traditional Haitian upbringing inside his home. “It was like living in two different worlds,” he says. That duality gave him a perspective that feels both deeply Haitian and uniquely diasporic. “I wasn’t fully in either. I spent a lot of my life observing, which really shaped me as an artist. My work comes from that—from observation of the world around me.”

Watson Mere always had difficulty with articulating words as a child. Unable to speak, Mere was encouraged by his parents and school teachers to utilize images and drawings to communicate his needs. By age five, when he learned how to speak, art was already his way of making sense of the world. His inability to speak heightened his sense of observation and taught him how to translate emotion and perception through visual form. Art has been his first and most enduring language. “Art was my communication,” he remembers. “It’s what I used before I even had words.”

His artistic instinct never faded. When his parents brought home a computer, thirteen-year-old Mere discovered Microsoft Paint and found himself transfixed. He taught himself to create with the program, developing a style that would carry him for years. “That was my vehicle,” he says. “I drew every day, and learning how to paint digitally is what really helped me refine my skills as an artist.” His father, a church musician, also deeply shaped his discipline. “Every day, no matter what was happening, he made time to practice his music. I saw that and understood: if you love your craft, you show up for it daily. That stuck with me. Until this day, the lesson that he taught me remains: I make time to create art every day, no matter what.”

Inspiration for his artwork does not arrive as concepts, but as revelations. “People call them ideas, but for me they’re visions,” he explains. “If I see something that makes me feel deeply, I have to paint it.” The process can take months. A vision may start one way, then evolve as his life and the world around him shift. Sometimes his pieces feel like journals, layered with personal and political context. Music often sparks the visions, but water does too — even the sound of a sink being turned on can set the ideas in motion. “These situations just do something to my brain and visions come to me,” he says. Mere sees his work as a portal that reflects on the experiences of his audience. He offers a glimpse into worlds his viewers may have never seen or understood. He aims to create art that resist passive observation and invites others to engage, reflect, and question their beliefs. Mere's creative practice is rooted in the cultural complexities of the African diaspora. He is driven by a desire to give a visual voice to those long silenced by social expectations, a mission born from his own early voicelessness. He also carries a piece of advice from his mentor that he passes on to young artists: “Move with no fear. No fear of judgment, no fear of putting your art out into the world. Whatever your spirit is telling you to do — move toward it without hesitation. Move with no fear.” Mere also carries a piece of advice from his mentor that he passes on to young artists: “Move with no fear. No fear of judgment, no fear of putting your art out into the world. Whatever your spirit is telling you to do, move toward it without hesitation. Move with no fear.”

Watson Mere | GOLIATH, 2023 | Acrylic on Canvas

Theater also deepened that sense of revelation. Cast in a New York festival production as Sango—the Yoruba deity of fire and thunder— in The Fourth Aladdin of Oyo by Taiwo Aloba, Mere found himself transformed by performance. Stepping into theater gave him a lasting impression, and his practice took a dramatic turn. The play won “Most Creative” at the New York Theater Festival, and the role pushed his art toward new terrain. “It was intense,” he says. “Becoming that character inspired me deeply. Right now I’m working on pieces incorporating elements of that character. My pieces have these walls of fire, that are loosely based off that deity.” That fire has become both metaphor and motif. Growing up, he watched sugarcane fields set ablaze as part of the harvest cycle, destruction that was also renewal. “Fire looks chaotic, but it’s also purification,” he reflects. “That’s how I see the world right now. Everything feels like it’s burning — politically, spiritually, even in the art world. But sometimes you need the fire for something new to grow. Sometimes the “Djab” (demons) need to show their faces so the world can come together and say “that’s not what we want - let’s try something different, something better”

Watson Mere | Sango Baba Wa, 2023 | Acrylic on Canvas

Carrying a Haitian identity in the U.S. comes with both power and pressure. “Haitian art is respected globally. Even outsiders understand its spiritual force. That history lifts you up,” Mere says. Yet with recognition comes expectation. “There’s a responsibility. As a Haitian artist, you carry something historic and powerful. At the same time, you’re often compared to Basquiat, even if your work is completely different. And because the news about Haiti is always negative, you feel a duty to respond, to defend your country. The ancestors gave us this gift — I feel it’s my job to use it.” He has already begun laying the groundwork towards his future goals. During his residency with Haiti Cultural Exchange in Brooklyn this past year, he led workshops for young Haitian artists, focusing not only on technique but on professional development — writing resumes, applying for grants, and navigating the business side of art. “I didn’t go to art school; I have a degree in Master Business Administration. That experience offered me a sense of the business side of things, which is just as important. A lot of great artists struggle because they don’t have that knowledge.” Mere’s long-term vision extends beyond his own career in New York City. “One of my main goals is to return to Haiti and build an art school,” he says. “I want to find children with the gift, guide them, and help send them into the world. That’s how we keep this tradition alive.” Mere dreams of projects and exhibitions in Haiti that will bring together visual artists, playwrights, poets, and photographers. “We need all of our soldiers,” he says. “We need to come together to find solutions for our country.”

Photography by Richard Louissaint

“Move with no fear. No fear of judgment, no fear of putting your art out into the world. Whatever your spirit is telling you to do — move toward it without hesitation. Move with no fear.”

— Watson Mere

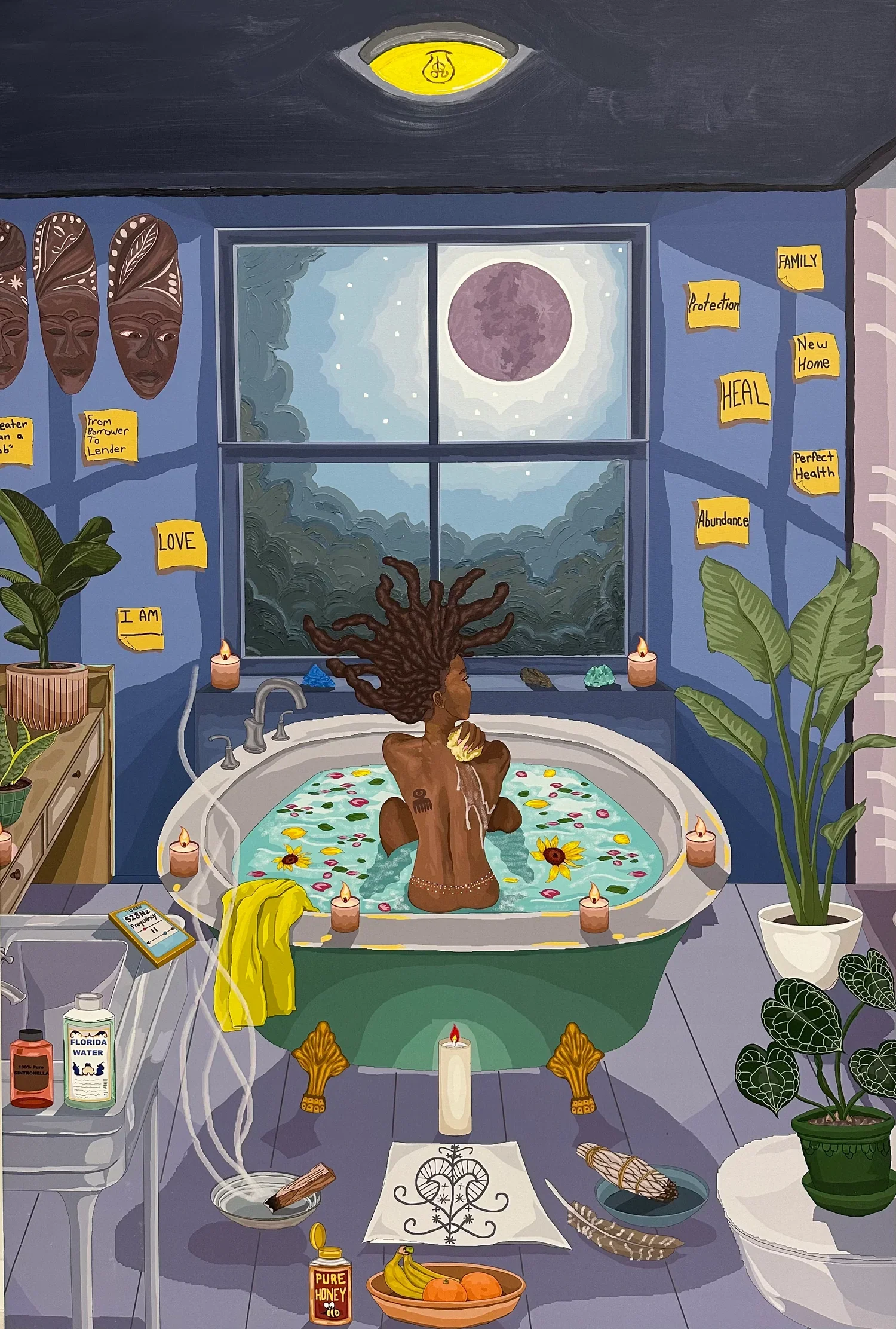

Protection

Like Georgia Clay in the Mornin

BonQuisha's Ritual

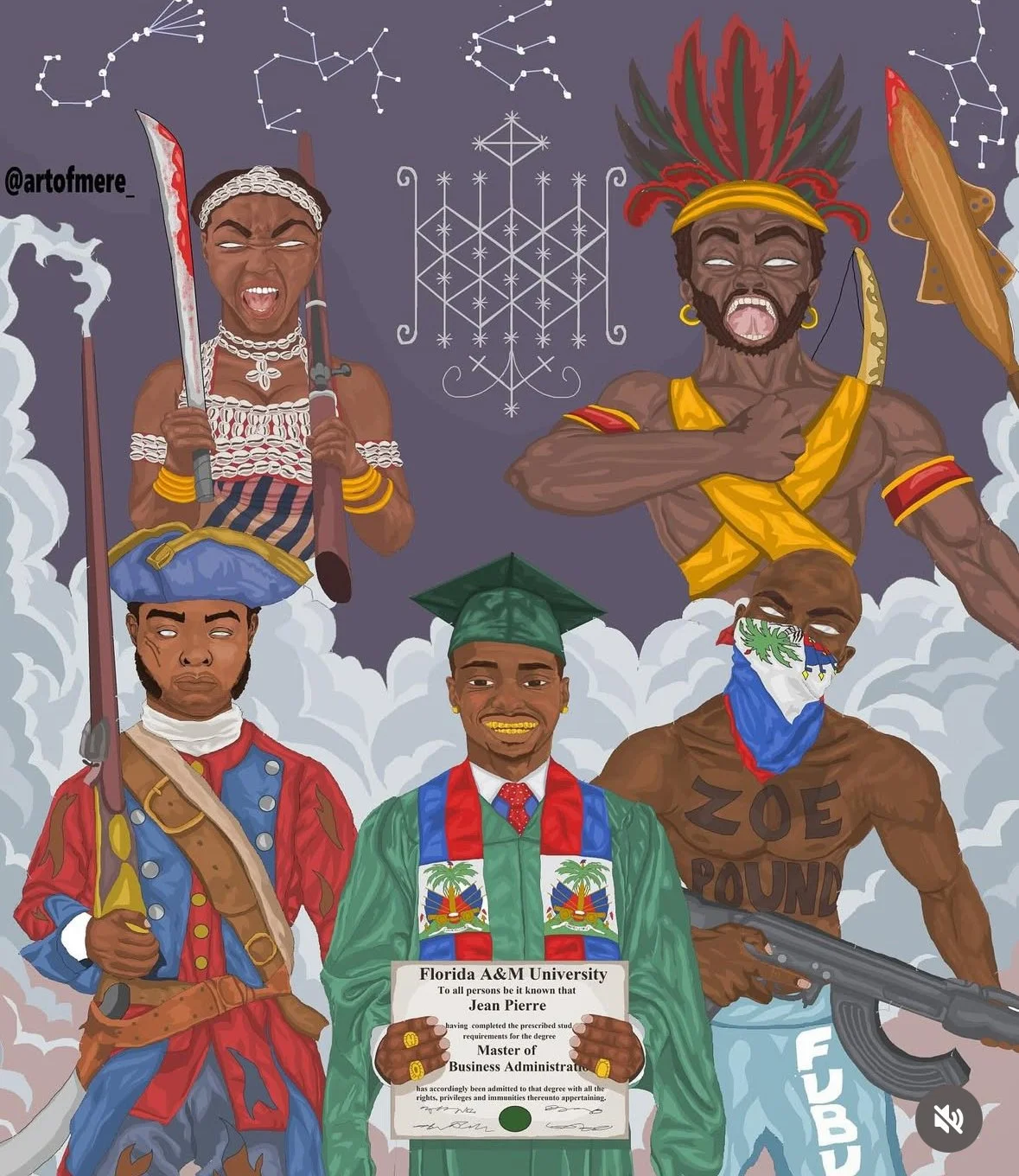

Descendants of Might

The Great Hypocrisy

My Brother's Keeper